An Exclusive Interview with Mike Carey

Mike Carey is a highly in-demand writer at the moment, with his current comic book projects including his new Vertigo series, The Unwritten, and at Marvel, X-Men: Legacy, Ender’s Shadow: Battle School, and an upcoming X-Men Origins: Gambit one-shot. In conjunction with his comic book work Mike also writes a series of popular novels about Felix Castor, an amoral exorcist for hire in an alternate London where the dead just won’t seem to stay dead!

Mike Carey is a highly in-demand writer at the moment, with his current comic book projects including his new Vertigo series, The Unwritten, and at Marvel, X-Men: Legacy, Ender’s Shadow: Battle School, and an upcoming X-Men Origins: Gambit one-shot. In conjunction with his comic book work Mike also writes a series of popular novels about Felix Castor, an amoral exorcist for hire in an alternate London where the dead just won’t seem to stay dead!

Despite his incredibly busy schedule Mike was kind enough to take some time out of his indubitably hectic weekend to discuss his currents project with me:

Hi Mike, thanks very much for taking the time out to do this interview. It is greatly appreciated!

The first Batch of questions that I want to ask you are about your new Vertigo series, The Unwritten:

- What inspired you to begin work on The Unwritten?

MC: There were a lot of things that came together, really – and the inspiration was as much Peter’s as mine. We each separately came up with an idea for a new book, and we threw them at each other at roughly the same time. Peter’s was about a child who is also the protagonist of a series of books, with the action of the comic tacking between the reality and the fiction. Mine was about the trumpet that sounds the end of the Yuga, the current age of the world. The third element in the mix was Christopher Milne’s autobiography, in which he talked about the burden of being Christopher Robin in the Winnie the Pooh books. Somehow all these things cross-fertilised and became The Unwritten.

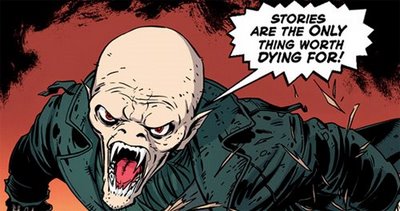

- The ‘blurb’ for The Unwritten says that “Tom must search through all the places in history where fiction and reality have intersected. And in the process, he’ll learn more about that unwritten cabal and the plot they’re at the center of —- a plot that spans all of literature from the first clay tablets to the Gothic castles where Frankenstein was conceived to the self-adjusting stories of the Internet”. It sounds to me like you are planning to explore the common roots of all stories and mythology? Is this a correct assumption?

MC: Picking my words with care here… We’re interested in the “use value” of stories, and we make the assumption that that has been fairly constant across cultures and across times. We will, very definitely, be raiding the stories of different ages and societies, going back to some of the earliest narratives that have come down to us from the first cultures that had written languages. So if by common roots you mean the impulse in the human spirit that leads to stories, yeah, we will be standing up on our hind legs and pitching a theory about that. But it’s not an ethnographic theory, ultimately – it’s more a psychological theory.

- One of the things that Tom Taylor does is in the comic is picture the fictional geography of the World. That is, he points out places where events in literature took place, or things which inspired literary concepts? An example in the first issue is his remarking that the Senate House, in London, where George Orwell worked at the Ministry of Information, was his model for the Ministry of Truth in 1984; also, that Pianosa was the setting for Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. Is this something that will be playing into the story? The thin wall between reality and fiction? Also, is this something you took from your own life, or that of someone you know? Because it is something that my Wife and I do all the time. I thought perhaps we were the only people who were interested in such literary trivia

MC: The idea that individual stories have a home, a natural soil, is something that we play with a lot in the book, and it does become a central element – as the inclusion of the Waldseemuller map on the last page of Unwritten#1 hints. It’s not something I do myself, but I have a very good friend who does it. Speaking personally, I’m generally unstuck in both time and space. But when I find myself in a place that has resonances like that, it really has a powerful effect on me.

- In the debut issue of the series, the protagonist Tom Taylor remarks that similarities have been drawn between the stories of his fictional namesake Tommy Taylor, and other fictional works such as the Harry Potter books, The Books of Magic, and The Worst Witch. The current trend is to label all child-related fantasy stories as derivative of Harry Potter. However, the story of a child that is bestowed with great powers and great responsibilities is one that has very deep roots in literary history. It is a story that has been reiterated many times, and appears in many popular works of fiction. Examples include: Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, in The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings respectively; Paul Atreides and Leto II in the Dune saga; Rand Al Thor in The Wheel of Time books; Harry Potter… the list goes on. What do you think is so powerful and fascinating about this type of character, and why do you think that it can bear so many reiterations? Is this something that you plan to explore with Tommy Taylor in The Unwritten?

MC: It’s one of the archetypal story springboards, as you say, and once you’re sensitised to it you tend to see it everywhere. I suppose it’s one dimension of the bigger, broader narrative edifice that used to be called the bildungsroman – ie, stories that centre on the development of a child into an adult, tracing the formative experiences that leave their mark on him along the way. But it goes back before that term and before that trend, way into myth and folktale. Maybe it speaks to something we all feel when we face the world and try to fit ourselves into it. We experience ourselves both as belonging and as unique.

- In the first issue, we see the first hints of a religion that starts to sprout up around the revelation that Tom Taylor is really the fictional character Tommy Taylor made flesh. Is this something that you plan to explore in this series? Fiction made religion, and religion made fiction?

MC: As Wilson’s notes on that final page say, religions and mythologies are stories – stories with exceptional power and exceptional tenacity. In that sense, it doesn’t matter (to what we’re doing, anyway) whether they’re true or not. We’re interested in how they’ve touched the world and the marks they’ve left on it.

MC: When we wrote Lucifer, we purposely left Christ out of the picture. In The Unwritten we’ll have occasion to mention him. It would be kind of crazy, in a way, to write a book about the power of stories and to leave out the stories that have had the biggest influence on human history, many of which would be the core stories of the world’s religions.

- I have read that you are an atheist. However, many of your stories seem to explore religions themes. I am an atheist myself, but I must admit that most of the fiction that I read seems to involve the mythology of various religious belief systems. Why do you think that as atheists we still have an attraction to religious stories. Do you think atheists have a different perspective of these tales, and can read them in a less objective way?

MC: Actually, this was a conversation that Peter and I had several times while we were planning and pitching the series. He said – and I agree – that it’s really remarkable the way atheist and humanist writers return to religious and mythological themes in their work, without feeling any sense of incongruity or moral compromise.

MC: Part of the explanation for me is that although I’m an atheist now, I grew up saturated in Judaeo-Christian stories – at school, at Sunday school, at home – and because I met them when I was a child, and maximally receptive to stories, they’ve never lost their power for me. That’s probably true for a lot of people. Then there’s the fact that you know, when you refer to these stories, that a large proportion of your audience will read them with some of the same familiarity and some of the same complex of feelings: they’re hugely valuable cultural reference points.

MC: And at rock bottom, although I can’t believe in a personalised god, or gods, I believe in and value the numinous – the sense of being in the presence of a power greater than yourself. Religions, even if you think they’re moonshine, can be a shortcut to that sense.

MC: It’s all about belief. I’ve stolen a quote from Wallace Stevens somewhere, to the effect that in the end, you have to believe in a fiction: you only get to choose which one.

Let’s talk a little about your current work on X-Men: Legacy and your upcoming X-Men Origins: Gambit…

- Since the finale of ‘Messiah Complex’, X-Men: Legacy has been about Professor Charles Xavier embarking on a journey to recover his lost memories. The current ‘Salvage’ story arc has seen this emphasis change slightly. The story has seen Danger taking Rogue through her past and forcing her to confront certain aspects of it. Do you plan to keep the emphasis on either of these characters, or is the focus going to be changing altogether? Will we see any other characters facing their past mistakes and learning from them?

MC: The book is about to metamorphose into something very different, with Rogue taking the centre stage and Professor X bowing out. His quest gets its coda in #225, and then we enter the next phase of the title. But it’s not a repetition of Xavier’s odyssey with another character in the driving seat: I think that would be a really bad idea. What we’re doing is putting Rogue in a new role in relation to the X-Men, and playing that logic out – probably for a year or so, as we did with Professor X. It’s going to be fun, because of the possibilities this new role opens up. It lets me play with a lot of characters who I like a hell of a lot.

- Much of your X-Men: Legacy run has involved characters searching their memories and facing past events. This has often involved working in the interstices between established continuity. This is clearly something that you have researched very thoroughly, but have you encountered any difficulties doing this? Being bound by the confines of pre-established events.

MC: Well, there are the logistical difficulties, of course. It’s not always easy to get hold of the original stories and get chapter and verse. If you’re not careful, you can find yourself retconning without meaning to. But I don’t think I’ve ever found past continuity constraining in these stories. I’m always going with the grain of what was there before. That’s my natural instinct in any case. When I take over a book that’s existed for a long time already, I don’t tend to explode off in a new direction. I match velocities, then gradually introduce my own themes and ideas as I go.

- Gambit is character that has featured heavily in the recent events of X-Men: Legacy. It was recently announced that you are going to be writing X-Men Origins: Gambit. I find Gambit is one of those characters that tends to polarise people. Some people love him, and some people seem to despise him. What is it about him that you find so compelling?

MC: Thieves, rogues and vagabonds are usually fun to write – the more so when they’re thrown into the company of better-behaved and more conformist characters. When Gambit joined the X-Men, most of them had a very strait-laced morality. That’s no longer the case, and he doesn’t stand out so vividly now as he did then, but he’s still a great wild card. And yet part of the appeal is that – although it’s way outside accepted social norms – he does follow a very strict code. He’s not amoral in any sense: he just puts the boundaries in different places from most other people.

- Personally, I find that when Gambit is written well, he is a character that I really enjoy reading, but I find that too many times in the past people let him fall into that southern red-neck rut and make him out to be a bit of a hick. You seem to write him as a much more intelligent character, and make him much more three dimensional, playing more of an anti-hero. Is this something that you set out to do when he joined the book? To better define the character?

MC: Well, to revisit what was fun about him in the first place – to define the aspects of Gambit that I like and get a kick out of. And yeah, giving him a shrewd intellectual edge is definitely a part of that for me. Gambit needs to be cunning: all the best thieves, it seems to me, ought to have great tactical minds.

- What period of Gambit’s life does the one-shot cover, and will this be tying in to current events that are happening in X-Men: Legacy?

MC: It covers the whole period from the day of his wedding to the day when he runs across the X-Men by saving Storm from the minions of the Shadow King. It ties together a lot of things that we already know about his past, but that haven’t ever been put together as a single narrative.

MC: There’s no real connection to the Legacy stories, except insofar as knowing about a character’s past enriches your appreciation of their current actions and decisions.

- Something that you are especially known for is taking underused, or misunderstood characters and making them into key players within the Marvel Universe. This has been seen with characters such as Iceman, Rogue, Charles Xavier, and now Gambit. Characterization seems to be a top priority in your stories, and you seem to have a knack for figuring out what makes these characters tick, and then highlight those qualities in a most expert manner. How do you approach this?

MC: Thanks for the compliment. Paradoxically, I think if I get these things right it’s because when I was starting out as a writer I used to put the emphasis way too much on plot, and make character serve plot to a crazy extent. I learned the hard way that character has to be the catalyst that makes everything else happen.

I don’t deliberately choose obscure characters, though. I choose characters who I think I can write in an interesting way, or characters whose stories I really want to add to. Sometimes I grab a character because nobody else is using them and they just seem to be screaming out to be used. Lady Mastermind and Karima Shapandar would fall into that category.

- Fair enough! Perhaps it is more a case of some other writers chosing to use characters that have a good track record of popularity. Not wanting to take a risk on using characters they find interesting but are not instantly recognizable.

Also from Marvel comics, you are currently working on an adaptation of Orson Scott Card’s novel, Ender’s Shadow…

- How did you become involved with Ender’s Shadow: Battle School?

MC: I was invited to pitch, and I was very happy to do so. I think both Ender’s Game and Ender’s Shadow are very fine novels, and I’d had a really rewarding experience when I wrote the comic book adaptation of Neverwhere. I was quite keen to stretch those creative muscles again.

- How familiar are you with Scott Card’s Ender/Shadow saga? Are you a fan?

MC: I’ve read all the books except the latest, Ender in Exile. I don’t enjoy them all equally, but any sequence of novels that includes one genre-defining masterpiece and two other books that are great in their own right has to be worth following all the way to its end point.

- I haven’t actually read Scott Card’s original novels myself, which is a bit of a sci-fi sin, but I have been quite enjoying Marvel’s adaptations. I must look those books up. I am however a big fan of his less popular series of Alvin Maker books. I highly recommend them!

- Are you going to be involved on any future adaptations based upon the series?

MC: I’m not aware of any plans to follow up these two adaptations, but I’d be up for it if I was asked.

Outside of your regular comic book work you have been doing a lot of work on your series of Felix Castor Novels…

- Some readers, particularly those in North America, may not be as familiar with your prose work as your comic book work. How would you describe your series of Felix Castor novels to someone who has never read one before?

MC: They’re stories about an exorcist – but an exorcist who’s presented in a sort of Raymond Chandler style. Castor isn’t a man of faith: he does it for the money, wears a longcoat and walks the mean streets. He has a knack, an inborn ability which allows him to dispel ghosts and demons, and he uses it to earn a living. He’s not unique in this: there are a lot of exorcists around, although they all use different techniques to do the job. Castor uses music: he plays tunes on a tin whistle, and the tunes have the power to bind and banish the dead.

MC: This is in a London that has seen a sudden upsurge in hauntings and supernatural manifestations of every kind, so the kind of skills that Castor has are very much in demand. But it’s a dirty and dangerous job: a job that doesn’t have a retirement plan because nobody lasts long enough to need one.

- I have heard some readers draw parallels between the character of Felix Castor, and that of John Constantine. There are certain similarities, such as them both being magic users, who have made bad decisions in their pasts, which they have been paying for ever since. Would you say that this character was at all inspired by your time writing Hellblazer? Also, what do you think makes the character distinct and unique?

MC: This is a tough question for me to answer, because there is a link between Castor and Constantine – but the link is me, if that makes any sense. Both men are Scousers living in London, and so am I, so I use my own experiences as reference when writing both of them. But that’s only the starting point, and I think the characters diverge pretty markedly after that.

MC: Castor is defined, as a character, by the first exorcism that he performs, and by his delayed reaction to it. He’s somebody who is expiating a very specific sin. He maintains a cool and cynical façade, but actually he’s driven by two needs: the need to atone and the need to understand. They both get him into deeper and deeper trouble as the series goes on.

MC: Another important difference is that Constantine lives a slash-and-burn kind of life: he’s a man who constantly abandons his baggage and accumulates very little. Castor has a fixed set of relationships and a fixed sphere of action. There’s a small circle of people (entities, rather) who are crucially important in his life – who own a piece of him. Nobody owns Constantine: that’s his gift and his curse.

- I can definitely see the differences myself. They do sound quite similar on the surface, but once you get into their stories, they become markedly different characters.

- I have read the first two Felix Castor novels (The Devil You Know, and Vicious Circle) and I enjoyed them very much. I think that these books are some of the best writing that you have ever done and I am eagerly waiting for the North American release of the third book in the series, Dead Men’s Boots (released July 23rd 2009). In the UK the fourth book in the series, Thicker than Water, has just been published with book five, The Naming of the Beasts to follow later this year. What is the major reason behind the delay in the North American releases of the books?

MC: I think it’s mainly that the two markets work in different ways. Each US release has to have a hardcover and then a mass market edition, and that process has its own rhythm which seems to be fairly inflexible.

- Are there any tentative release dates for books four and five yet for North America?

MC: So far there isn’t even a contract. The contract with Grand Central covers the first three books, just as my first contract with Orbit did. We’ve yet to talk turkey about the fourth and fifth books. I’m assuming, though, that we’ll just agree to extend the existing contract and carry on according to the same schedule, with one Castor a year coming out in the US.

- Hmmm, it looks like I might have to head over to Amazon.co.uk and get them sent over to me in Canada. There’s no way I can wait that long

- I have been trying to avoid reading spoilers, but one think I have heard from friends is that you left Thicker than Water on quite a tense cliffhanger moment. Have many fans been very vocal about this?

MC: There is a crucial dangling plot thread, yeah. The main plot wraps up, as it does in each of the Castor books, but this time there’s a sting in the tail relating to one of the other core characters, and it doesn’t get resolved until Naming of the Beasts. Most people I’ve spoken to have enjoyed that bait-and-switch aspect of the story. Nobody’s threatened to lynch me yet.

- Book Five is titled The Naming of the Beasts. This sounds very final and climactic. Is it intended to be the final book in the series? Or can we expect to see further adventures of Felix Castor?

MC: It’s emphatically not the final book. There has to be at least one more, as yet untitled, which will resolve the overarching mystery I began to tease in Dead Men’s Boots – the mystery of why the dead are rising and how all the various supernatural elements in Castor’s world fit together.

- Excellent, I’m glad to hear that! As I previously mentioned, I have only read up to book two, so haven’t yet encountered this overarching mystery…. now I really need to read that book!

- Have you ever toyed with the idea of doing a Felix Castor comic book?

MC: I’ve thought about it, but I keep coming up against the same intractable problem: how do you draw music? What Castor does is easy to dramatise in a prose novel, but it would be a tough proposition in a comic book.

- Ah yes, that is a very good point, I hadn’t thought of that!

Well, thanks for your time Mike, that was a LOT of questions I asked you, and you gave some rather in-depth answers! Keep up the great work!

If you would like to keep up with what Mike is doing, make sure to bookmark Mikecarey.net where you can find out the latest about Mike’s releases, talk with fellow fans, and much more!

No related posts.

Comments

One Response to “An Exclusive Interview with Mike Carey”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying about this post...[...] you have not read the interview I recently did with Mike, I recommend you do so now. We talk primarily about The Unwritten, amongst other projects that he [...]